After musing on the battle of Mansfield in my previous post, I come to the question of whether Banks was on the wrong road. The basics of the situation are this: by the first week of April 1864 U.S. forces had advanced as far as Grand Ecore and Natchitoches; it was about 75 miles further to Shreveport, the ultimate target; Banks chose to follow a road that swings west away from the river. In several books on the campaign, authors have described this as a critical decision point (in fact the descriptions come across as a little too similar at times as if they are all following the same script).1 These authors claim that it was a serious mistake not to take a road along the river. But I am not convinced that this issue has been adequately analyzed.

How do we know the “river road” from Grand Ecore to Shreveport was really any good? From my reading of the books on the campaign, there are two sources for the existence of the “river road” — one descriptive and one cartographic. The first comes from a letter that Admiral Porter wrote to General Sherman a week after the battle of Mansfield:

“While all the fighting was going on on shore the fleet was slowly and painfully working its way up Red River, through snaggy bends, loggy bayous, shifting rapids, and rapid chutes. … It struck me very forcibly that this would have been the route for the army, where they could have traveled without all that immense train, the country supporting them as they proceeded along. The roads are good, wide fields on all sides, a river protecting the right flank of the army, and gunboats in company. An army would have no difficulty in marching to Shreveport in this way.”2

The problem is that Porter only observed a limited stretch of the river so he could not know how good the road was for the entire length to Shreveport. I also think it is interesting to see how he describes the passage of the river in this area.

The second source cited for the road along the river is the Confederate map (or versions of it) shown here: Map of the Red River campaign, March 10-May 22. 1864. Clearly it does show a road along the river. However I see four challenges with what appears on that map.

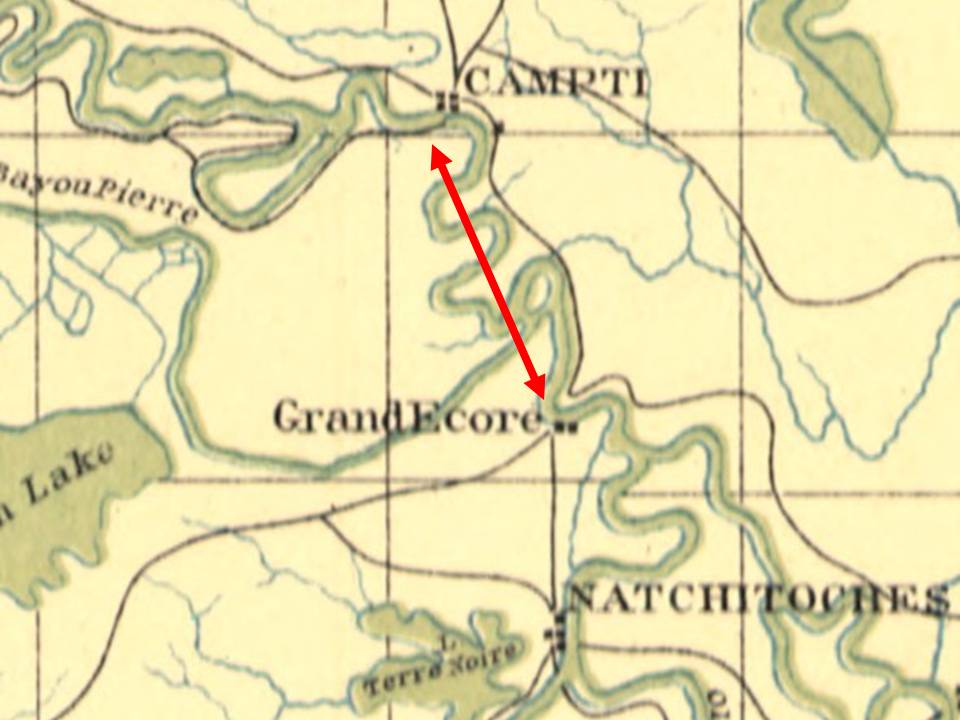

1) The road doesn’t start at Grand Ecore (see detail below). To get to the road, the US army would have to cross the river at Grand Ecore and move up the north bank to Campti, then cross back over the river.

2) By following this road, the army would be constrained between the Red River and Bayou Pierre. Confederate General Richard Taylor described Bayou Pierre as frequently expanding into wide lakes, 300 feet wide at the narrowest and never fordable.

3) The final approach to Shreveport is a mess (see circled area in detail below). The road crosses the river about 4 times before joining the road from Mansfield as it enters Shreveport from the south.

4) About 20 miles south of Shreveport is a loop in the river known as Scopini Cutoff and a short waterway called Tone’s Bayou that links the Red to Bayou Pierre (see arrow in detail above). Not only does the road cross the Bayou — requiring more bridging and ferrying — but the Confederates had built fortifications there, something that I will explore in the next post.

There is also another reason for Banks to choose the road to Mansfield. In his order to Gen. Franklin regarding the march, Banks stated that he wanted to meet the enemy in battle before he could retreat to the fortifications of Shreveport or into Texas. It was known that Taylor was along the road through Mansfield. So is was logical to go to where the opponent was rather than follow a different road.

With these thoughts in mind, I don’t buy the standard line that the decision to take the road to Mansfield instead of one along the river was a critical mistake.

—

- For example see Johnson, Red River Campaign: Politics and Cotton in the Civil War, p.113-115; Joiner, One Damn Blunder From Beginning to End, p75-78; Brooksher, War Along the Bayous, p. 75; and Anders, Disaster in Damp Sand, p.44-48 . ↩

- Official records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion, Volume 26, page 60 ↩

.jpg)

0 responses so far ↓

There are no comments yet...Kick things off by filling out the form below.

Leave a Comment