Smith & Wesson is now a giant in the firearms industry, but New England gunmakers Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson didn’t start that way. In fact, their first efforts ended in failure. In 1853 Smith & Wesson patented the “rocket ball,” a conical lead ball with a hollow base filled with power having a primer at the base, derived from an earlier design. The next year they set up a factory to manufacture a pistol to use it, which came to be called the Volcanic. To get around Samuel Colt’s revolver patents they made the pistol lever operated with a tubular magazine under the barrel. It was not exactly a roaring success-the rocket ball was grossly underpowered and the gun prone to malfunctioning, making it more of a geeky curiosity than a serious firearm. The firm struggled along until 1855 when it was bought out a group of investors, who did no better and eventually went bankrupt. One of them, a local shirtmaker named Oliver Winchester, bought the company’s assets and through the efforts of his foreman, one B. Tyler Henry, ended up with something entirely different. If the Volcanic looks familiar it should—Henry scaled up the action, simplified the toggle-link lever action loading mechanism, married it to a .44 caliber rimfire cartridge and made it into the well-known Henry rifle, which in turn begat the Winchester of Old West fame.

There are a couple of YouTube videos showing the loading and firing of a Volcanic pistol.

Smith and Wesson wanted to make pistols, however, and specifically revolvers. Colt’s revolver patents expired in 1856, which made things easier, but the partners needed something more to give them an advantage. Ironically they got it from a former Colt employee, Rollin White. This was the era, remember, when the cap and ball revolver was king. Samuel Colt had invented the first practical revolver, which used a five or six shot revolving cylinder. However each chamber was closed at the end and had only a small hole for the fire from a cap, mounted on a nipple on the outside of the cylinder, to flash through. To load the gun you had to upend it, pour the powder into each cylinder in turn, then insert a round ball that was driven home with a loading lever. White’s idea was to bore the cylinder all the way through so that it would accept a one-piece metallic cartridge—the same sort of thing Smith and Wesson had been working on. Colt was not interested in White’s idea so he left the company and in 1855 patented it himself. Smith and Wesson bought the exclusive rights to the patent (paying White twenty-five cents per gun) and formed another company to manufacture their new revolver.

Their other major innovation, which the bored through cylinder made possible, was to use a one-piece metallic cartridge that contained powder, ball, and rimfire primer. The idea had been around since 1845 and had been used in Europe for the single shot Flobert “saloon pistol” (this did not refer to a bar but to its use as an indoor target practice gun). The Flobert used a small ball seated directly on a rimfire primer, which gave it barely enough moxie to punch through a paper target. S&W refined the idea and added in their experience with the rocket ball. The result was a rimfire copper cartridge with a charge of black powder and a conical lead bullet all in one piece. This also solved the problem of obturation i.e. the leakage of combustion of gasses back toward the shooter. This had been a problem with all breech-loading arms, and there had been any number of more or less successful systems to contain it. S&Ws was simple and reliable—the soft copper expanded against the cylinder wall when the bullet fired, sealing it against blowback. The design was also inherently waterproof, giving it a marked advantage over cap-and-ball firearms in wet weather.

Nevertheless the first S&W cartridge was not exactly a magnum—it was only .22 caliber and delivered a wimpy 38 ft.-lbs. of energy at a muzzle velocity of about 785 fps. (Trivia: both the Flobert and the original S&W cartridge are still manufactured as the .22 BB Cap and the .22 Short, making them the oldest continuously-produced cartridges.)

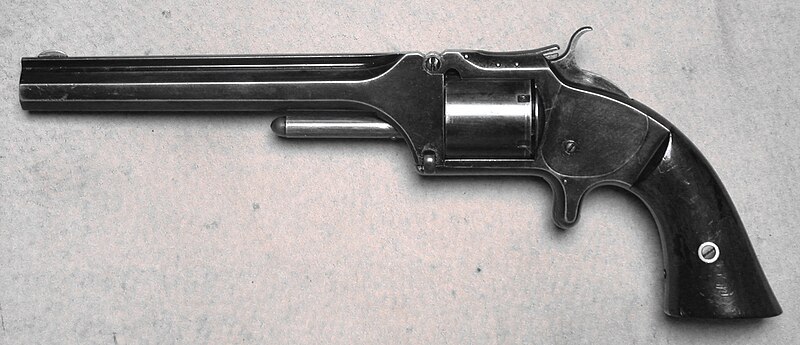

In 1857 Smith & Wesson rolled out their new seven-shot Model 1 revolver, which although only .22 caliber was technologically far superior to anything else on the market. It made a dandy pocket pistol and in spite of its lack of power sold very well. To load the gun the shooter unlatched the barrel and tipped it up, then removed the cylinder. If there were fired casings in the cylinder he reversed it and pushed it against the ejector, a built-in spike mounted just under the barrel, to remove them. He then inserted the cartridges and replaced the cylinder, pulled the barrel down and latched it, and the gun was ready to fire. Although this sounds clunky today it was a vast improvement over the cap-and-ball system. The little pistol went through three “issues” (models) and remained in production until 1882.

Not satisfied with their first success S&W was working on another gun, the Model 2, a full size pistol which utilized a .32 caliber bullet. Holding six copper cartridges, it had about the same power as the popular .36 cal. Colt Navy and like its smaller sibling was weatherproof. Introduced just a few months before Fort Sumter, it was an immediate hit as soldiers of all ranks and anxious civilians stood in line to buy them. In fact it sold so well that S&W was forced to stop taking new orders in 1862 because they could not fill them.

Because of its military associations the Model 2 quickly picked up the nickname “Army” or “Old Army,” even though it was never officially adopted by the military. While the Federals never bought any at least one state government, Kentucky, procured 2600 for its cavalry and mounted infantry units. High-ranking officers like Ambrose Burnside and George Custer rated fancy engraved specimens, but company officers and common soldiers appreciated them also. One Union private, William Phillips, often carried his while on patrol at Petersburg as a backup, boasting that “I had a musket and a revolver that would take a man at 40 rods. I can hit a 3 inch ring 10 rods every time…it carys copper cartridges and can be loaded in 15 seconds.” The Model 2 remained in production until 1874 with over 77,000 being produced.

S&W rolled out what was to be an even more popular pistol, the Model 1½, in 1865. It rated the unusual designation because it was essentially a Model 2 scaled down to about the size of the Model 1. Holding five of the bigger .32 cal. cartridges, it provided an apprehensive public during the Reconstruction years with a powerful, concealable pocket pistol. Demand was already so heavy for their arms that S&W had to sublet much of the production of the Model 1½ to another firm. Some 127,000 were made and it remained in production until 1875.

Horace Smith and Daniel Wesson now had the success that had eluded them earlier. By 1865 both men took home salaries of $160,000 each, a huge sum for the time. It must have seemed especially satisfying to “D.B.” Wesson, who’d had to elope with his bride in 1849 because his prospective father-in-law thought he’d never amount to anything.

Leave a Reply